Abstract

Background

There are now hundreds of systematic reviews on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) of variable quality. To help navigate this literature, we have reviewed systematic reviews on any topic on ADHD.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, PubMed, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science and performed quality assessment according to the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis. A total of 231 systematic reviews and meta-analyses met the eligibility criteria.

Results

The prevalence of ADHD was 7.2% for children and adolescents and 2.5% for adults, though with major uncertainty due to methodological variation in the existing literature. There is evidence for both biological and social risk factors for ADHD, but this evidence is mostly correlational rather than causal due to confounding and reverse causality. There is strong evidence for the efficacy of pharmacological treatment on symptom reduction in the short-term, particularly for stimulants. However, there is limited evidence for the efficacy of pharmacotherapy in mitigating adverse life trajectories such as educational attainment, employment, substance abuse, injuries, suicides, crime, and comorbid mental and somatic conditions. Pharmacotherapy is linked with side effects like disturbed sleep, reduced appetite, and increased blood pressure, but less is known about potential adverse effects after long-term use. Evidence of the efficacy of nonpharmacological treatments is mixed.

Conclusions

Despite hundreds of systematic reviews on ADHD, key questions are still unanswered. Evidence gaps remain as to a more accurate prevalence of ADHD, whether documented risk factors are causal, the efficacy of nonpharmacological treatments on any outcomes, and pharmacotherapy in mitigating the adverse outcomes associated with ADHD.

Keywords: Child and adolescent psychiatry, ADHD, Systematic reviews, Epidemiology, Public Health

Introduction

There are hundreds of systematic reviews on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) of variable quality and with partly or fully overlapping scope. This literature is increasingly difficult to navigate for clinicians, researchers, and policymakers. We aim to make this large literature on ADHD more available by systematically reviewing the published systematic reviews on ADHD and highlighting recent reviews of high quality where there are overlaps.

Methods

We performed a meta-review [1] to systematically appraise systematic reviews and meta-analyses published on ADHD-related topics by adopting Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [2] (Supplementary Table S1) and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for umbrella review [3]. The study protocol was pre-registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42020165638).

Search strategy and selection criteria Table 1

Table 1.

Selection criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses on ADHD published in peer-reviewed journals 2. Search performed in more than one database including at least PubMed or Medline 3. Involvement of two or more reviewers at any stage of the systematic review | 1. Letter/Erratum/Protocols 2. No clear description of article selection process 3. Quality assessment of included studies not performed 4. Same article published in different journal 5. No full text available (after rejection from authors) |

We searched MEDLINE, PubMed, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science for studies, using specific keywords (ADHD, systematic review, meta-analysis, see Supplementary 1 for a description of the search strategy) with no language restrictions. The search included all years and final search was completed in December 2021. Reference lists of included publications were also searched. All references from the literature search were imported to Endnote X7.2 [4] and then to Covidence [5]. Two reviewers (A.C. with I.L. or O.N.) independently performed title and abstract screening of all articles identified through database search and full-text screening of more than 95% of articles. Any discrepancies in assessments were resolved in consensus or by consulting the third reviewer or the last author (A.M.). To avoid overlap, when systematic reviews studied identical topics and included more than 50% of the same primary articles, we included only the latest reviews with more studies. The included latest systematic reviews and meta-analysis were of similar or high quality compared to the older reviews of same topics (Supplementary Table S2).

Quality appraisal and data extraction

The JBI guideline for quality appraisal and form for data extraction of systematic review and meta-analysis [6] was amended and piloted for the purpose of this meta-review (Supplementary 1). The quality appraisal checklist consists of nine items. Reviews that scored less than six on low risk of bias were categorized as low quality and excluded. Reviews scoring six to seven, and eight to nine were categorized as moderate and high quality reviews, respectively, and were included. Two reviewers (A.C., I.L.) independently assessed the quality of 35% of the systematic reviews to ensure consistency in the quality assessment rating. There was good agreement in quality assessment, and consequently, the remaining 65% of included studies were scored for quality by one author only. A similar process was followed for data extraction, where three reviewers were involved (A.C. with I.L. or O.N.). For each eligible article, pre-defined information was extracted, including topic studied, objective, timeframe of database search, main findings with key estimates, implications for clinical practice and future research, and conclusions. Further details are in Supplementary 1.

Data presentation

We present the objective, main findings, and conclusions of each included systematic reviews and meta-analyses in tables dividing the literature into nine topics of ADHD. In the text, we describe the literature in terms of a narrative synthesis, where for some reviews we have also presented effect estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for some key findings. For overlapping reviews, we highlight results based on recency and quality. As the result section is dense, we have also included summary table that include major findings, limitations, and recommendation for future systematic reviews and meta-analyses for each topic.

Results

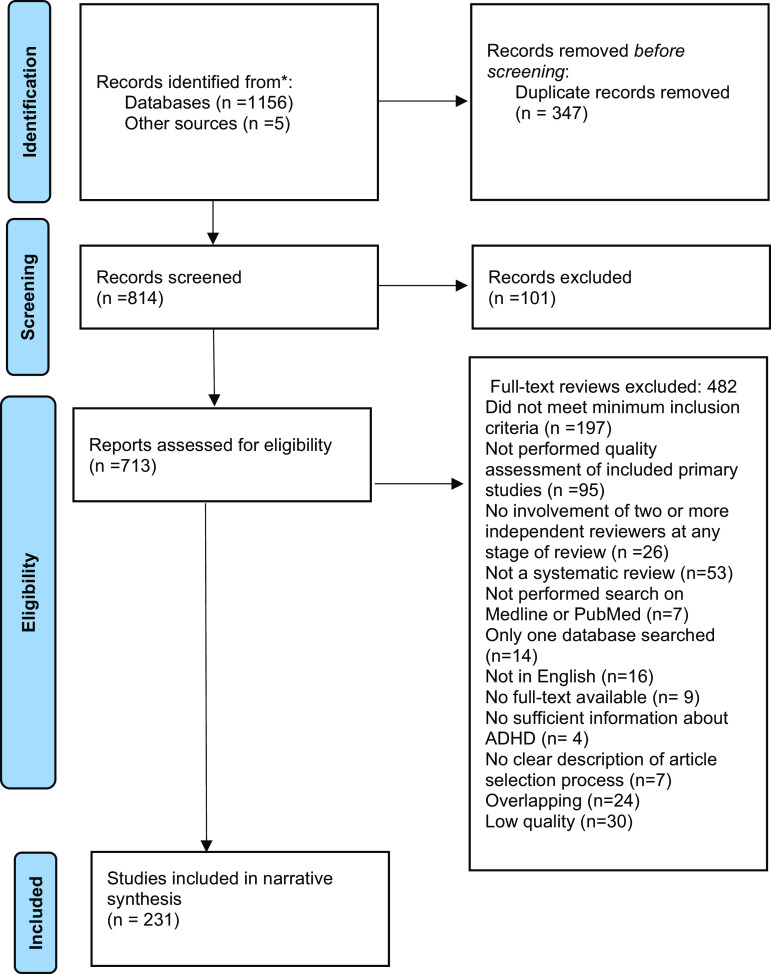

A total of 1,161 systematic reviews and meta-analyses were identified, where 231 were eligible for inclusion (Figure 1). The reasons for exclusions of each article selected for full-text review are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Characteristics and quality of included systematic reviews and meta-analyses

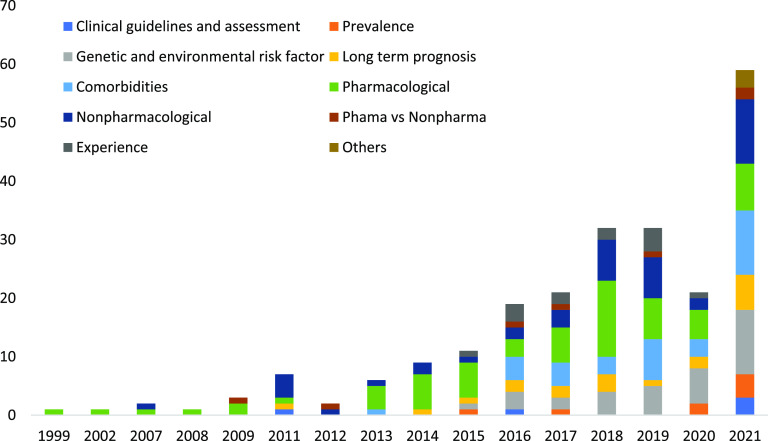

There has been an increase in published reviews annually with a very high number of reviews published in 2021. The most common topic for reviews was pharmacological interventions (28%) (Figure 2). Most of the studies included in reviews were conducted in Europe and North America (34 and 33%, respectively). Of the total included reviews, 59% were of high quality (Tables 3–11).

Table 3.

Clinical guidelines and assessment

| References | Objective | Keywords | Timeframe of database search | k | Sample size a | Analytical design | Main findings (Effect estimates, 95% CI) b | Conclusion and comments from the authors | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Razzak et al. [7] | Perform comprehensive review of clinical practice guidelines mainly emphasizing on diagnosis, evaluation and management recommendations for ADHD | Practice guidelines, Diagnosis | Not given | 5 | NA | Narrative synthesis | – The highest total score was achieved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines (91.4%) followed by the CPGs from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network – Good agreement across guidelines about the conceptualization of ADHD, and for stimulants as the preferred first pharmacological choice of treatment – Emphasis on rating scales, psychoeducational assessment and laboratory tests varied across guidelines | Improvements in the applicability of guidelines are needed to enhance its clinical use and relevance | Moderate (7/9) |

| Loyer Carbonneau et al. [8] | Identify sex differences among children and adolescents with ADHD on the primary symptoms of ADHD and on executive and attentional functioning | Sex difference, Symptoms, Cognitive deficits | 1997–October 2017 | 54 | Unclear | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate quality – Boys expressed more hyperactivity symptoms than girls did (g = −0.15, −0.33 to 0.03) and have more difficulties in terms of motor response inhibition and cognitive flexibility – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 80%) were observed across analyses | Future research should refine the profile of girls with ADHD and develop diagnostic criteria adapted to each sex | Moderate (7/9) |

| Chang et al. [9] | Examine the diagnostic accuracy of ADHD rating scales CBCL-AP and CRS-R in children and adolescents | Rating scales, Children and adolescents | Not given | 25 | Ranged from 18 to 763 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Of the total included studies,11 were of high quality, the rest of poor quality – CBCL-AP yielded moderate sensitivity and specificity of 0.77 (0.69–0.84) and 0.73 (0.64–0.81) respectively – Moderate sensitivities of 0.75 (0.64–0.84), 0.72 (0.63–0.79), and 0.83 (0.59–0.95) and moderate specificities of 0.75 (0.64–0.84), 0.84 (0.69–0.93), and 0.84 (0.68–0.93) were found for CPRS-R, CTRS-R and Conners ASQ, respectively – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 > 50%) was observed across analysis | Future meta-analyses comparing the diagnostic performance of two different tools should be conducted on the basis of studies that have directly compared the targeted tools by applying both tools to each participant or by randomizing each participant to undergo assessment by using one of the tool | High (9/9) |

| Staff et al. [10] | Determine the validity of teacher rating scales for assessing ADHD symptoms in the classroom | CTRS-R, SWAN, Clinical interview | 1980–January 2020 | 4: Clinical interviews scores, 18: Structured observation scores | Clinical interviews scores: 1,744 children, Structured observation scores: 2,203 children | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of studies were of high quality – Results showed convergent validity for rating scale scores, with the strongest correlations (r = 0.6, 0.5–0.7) for validation against interviews, and for hyperactive–impulsive behavior – Divergent validity was confirmed for teacher ratings validated against interviews, whereas validated against observations this was confirmed for inattention only – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 80%) were observed across analyses except for the meta-analytic correlations between rating scales and interview measures assessing inattention | Further studies with psychometric properties are needed to confirm validity of teacher rating scales | Moderate (7/9) |

| Taylor et al. [11] | Describe and evaluate the properties of different ADHD diagnostic rating scales in adults | Rating scales, Adults | Database inception to June 2010 | 35 | Not given | Narrative synthesis | – Majority of studies were of poor quality – CAARS and WURS, and the WURS, short version had the best psychometric properties among 14 included scales | Additional good quality research on CAARS and WURS including larger sample size are needed | High (9/9) |

Abbreviations: ASQ, Abbreviated Symptom Questionnaire; CAARS, The Conners Adult ADHD Rating scale; CBCL-AP, Child Behavior Checklist-Attention Problem; CPRS-R, Conners Parent Rating Scale – Revised; CRS-R, Conners Rating Scale – Revised; CTRS-R, Conners Teacher Rating Scale-Revised; k, Total number of primary studies included; NA, not applicable; SWAN, strengths and weaknesses of ADHD – Symptoms and Normal-Behaviors; WURS, Wender Utah Rating Scale.

a

Total participants included in the systematic review and meta-analysis unless otherwise indicated.

b

For findings from meta-analysis, if given effect estimates with 95% CI are presented unless otherwise indicated.

Table 11.

Patients’ and caregivers’ experience of ADHD beyond symptoms

| References | Objective | Keywords | Timeframe of database search | k | Sample size a | Analytical design | Main findings (Effect estimates, 95% CI) b | Conclusion and comments from the authors | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact on Quality of Life | |||||||||

| Lee et al. [226] | Compare children and parents rating for HRQOL for children with ADHD | Health related quality of life Informant agreement | 1970–August 2017 | 8 | 4,322 | Fixed and random-effect meta-analysis, meta-regression | – Included studies were of moderate to high quality – There was an small, but significant difference between parent–child rating of children and adolescents physical HRQOL (Hedge’s g = −0.23, −0.33 to −0.13), while moderate difference (g = −0.60, −0.71 to −0.48) for psychosocial HRQOL – Significant heterogeneity was observed across analysis | Future meta-analyses may include studies that recruit children with ADHD from the community to reduce selection bias | High (8/9) |

| Lee et al. [227] | Assess quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD | Health related quality of life, Parent–Child agreement | 1970–2014 | 9 | 8,020,867 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate to high quality – ADHD severely impaired children’s all three aspects of HRQOL: physical, emotional, and social – For HRQOL of children and adolescents with ADHD, no significant difference was observed between parent’s and children’s rating – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 80%) was observed across analysis | The mechanism through which HRQOL conceptualizations and subscales and family characteristics influence the parent–child agreement on ADHD children’s HRQOL, should be studied | High (8/9) |

| Experience with ADHD, pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions | |||||||||

| Eccleston et al. [228] | Synthesize adolescents experiences of living with ADHD diagnosis | ADHD diagnosis, Adolescents experiences, Qualitative | Database inception – February 2017 | 11 | 166 | Narrative synthesis | – Included studies were of high quality – Interpersonal conflict, stigma and rejection lowered adolescents “self-esteem” and “identity” in youths with ADHD, although positive aspects of having ADHD were also recognized | It is important to conduct research on diverse culture, ethnicity, religion and social class, to understand the experiences of different groups of people | High (8/9) |

| Wong et al. [229] | Synthesize perceptions of ADHD among children with ADHD and their parents | Illness perceptions, Common-sense model, Qualitative | Unclear | 101 | Not given | Narrative synthesis | The majority of children with ADHD displayed negative emotions, including shame, frustration, despair, and embarrassment, but some felt elated and joyful. Among parents, a much broader range of negative emotions was reported – frustration, stress, depression, guilt, helplessness, anger, loneliness; however, some of them felt relieved to find about the disorder | Research might be able to provide a more comprehensive understanding of perceptions of ADHD and their impact if they examine potential mediators and moderators and potential outcome of interactions between different level of ADHD | High (8/9) |

| Bjerrum et al. [230] | Synthesize adult experience of living with ADHD | Coping strategies Managing daily living, Qualitative | 1995–July 2015 | 10 | 159 | Narrative synthesis | – Included studies were of high quality – Adults with ADHD recognized the difference between themselves and others and hence struggle to fit into society Although adults with ADHD are creative and innovative, they found it difficult to arrange and complete daily life tasks. However, they find it to be rewarding and aimed to achieve a healthy balance in life through coping strategies | Research on the experience of ADHD adults from non-western countries are required | High (9/9) |

| Rashid et al. [231] | Summarize medication-taking experiences of ADHD patients and caregivers | Medications, Adherence, Qualitative | 1987–October 2015 | 31 | Not given | Narrative synthesis | – Included studies were of moderate quality – As children and adolescents with ADHD transition into adulthood, they become more autonomous and self-directed toward all aspects of medications, and their decision-making process is framed by “trade-offs” where the advantage and disadvantages of medications are considered | Future research should focus on family dynamics, including both siblings and parents, and how media portrayals impact ADHD perceptions and treatment | Moderate (7/9) |

| Moore et al. [232] | Synthesize attitude and experience toward school-based nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD | Nonpharmacological interventions, School, Qualitative | Unclear | 33 | 31 | Narrative synthesis | – Included studies were of high quality – Findings were categorized into four interrelated themes: “individualizing interventions”; “structure of interventions”; “barriers to effectiveness” and; “perceived moderators and impact of interventions.” In addition to ADHD symptoms, school-based interventions should consider the broader school context | Future research should also study how school-based interventions influence attitudes toward ADHD and peer-relationships | High (8/9) |

| Laugesen et al. [233] | Summarize the experience of parents of ADHD children | Child, Parents, Qualitative | Databases from their inception – April 2015 | 21 | Not given | Narrative synthesis | – Included studies were of high quality – Having a child with ADHD can be an overwhelming and stressful experience, and one can feel guilty, hopeless, and frustrated. Parents were stigmatized and blamed. Their personal and family routines became chaotic and they had to fight to get professional support for their children’s at both school and health services. However, they felt that despite these challenges, living with ADHD child was not all bad | Further research needs to explore how health professionals can support families and how future interventions can improve the competencies of health professionals and assist the families | High (8/9) |

| Martin et al. [234] | Assess the association between ADHD child sleep problems, parenting stress and parent mental health | Sleep problem, Parenting stress, Mental Health | Database inception – May 30, 2019 | 4 | Not given | Narrative synthesis | Sleep problems among children with ADHD led to higher parenting stress and negatively impacted parental mental health | Future research should control for potential confounders like child’s age, comorbidity to assess if the association is causal | Moderate (7/9) |

| Craig et al. [235] | Determine the coping strategies used by parents of ADHD children | Coping, Stress, Qualitative | Database inception – July 2018 | 14 | 3,024 | Narrative synthesis | Parents of children with ADHD often resort to an “avoidant-focused” coping strategy that is basically comprised of cognitive and behavioral activities aimed at avoiding direct contact with stressful demands, and is associated with distress and depression. In comparison to mothers of typically developing children, those with ADHD tended to seek more support and employ indirect methods | Future studies should study coping strategies in parents according to different subtypes of ADHD in children and also with other mental disorder | Moderate (7/9) |

| Societal and familial barriers to ADHD treatment | |||||||||

| French et al. [236] | To identify barriers and facilitators in understanding ADHD in primary care | Primary care, Qualitative | Database inception – January 2018 | 46 | Health professionals: 15,314 Parents: 134 | Narrative synthesis | – Majority of the included studies were of high quality – Findings suggest that “need for education,” “misconception and stigma,” “constraint with recognition,” “management and treatment,” and “multidisciplinary approach,” are the main factors influencing the acknowledgment of ADHD by primary care practitioners. A considerable need for improved education about ADHD among primary care practitioners was also found – Significant heterogeneity were found across studies | For more specific solutions, future research should study scarcity of resources, misperceptions, and multidisciplinary approaches in health care settings | High (9/9) |

| Gwernan-Jones et al. [237] | Explore the influence of school-context on ADHD symptoms | School-stigma, Attributions, Qualitative | 1980 – March 2013 | 34 | Not given | Narrative synthesis | – Majority of the included studies were of high quality – Teachers and students may be blind to the role that schools play in ADHD symptoms despite the fact that the potential for stigma-based discrimination in schools is known. This is because stigma-based discrimination criteria are implicit and seem normal and appropriate to those who belong to the group. The stigmatized individuals may experience emotional pain as a result of this lack of understanding, which may worsen the symptoms of ADHD. The implementation of school-based treatments may also be aided by awareness of these potential implications of the school context | Future qualitative research could examine modifications to the school environment, routines, and expectations, including support for connections between students and their teachers and peers | Moderate (7/9) |

| Ogle et al. [238] | Assess efficacy of psychosocial treatment among ADHD children living in poverty | Poverty, Psychological interventions | Unclear | 5 | 461 | Narrative synthesis | Mixed evidence exists about the impact of poverty on psychosocial treatment for children with ADHD | Future research with more accuracy, precision, and quality in the reporting of income data are warranted | High (8/9) |

Abbreviations: HRQOL, health related quality of life; k, total number of included studies.

a

Total participants included in the systematic review and meta-analysis unless otherwise indicated.

b

For findings from meta-analysis, if given effect estimates with 95% CI are presented unless otherwise indicated.

Overview of findings

The included reviews were categorized into nine different topics and the major findings for each topic are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary table of major findings

| Topics | Major findings | Limitations | Further reviews needed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical guidelines and assessment | Good agreement across guidelines for stimulants as first-line medication Psychosocial interventions was recommended despite lower degree of evidence | Although guidelines recommend rating scales as part of the assessment, they vary in their emphasis and recommendation of which to use | Future reviews of rating scales should include head-to-head comparisons of different rating scales, sex-specific symptom profiles, and functional aspects of ADHD beyond core symptoms |

| Prevalence of ADHD | The pooled prevalence of ADHD was 7.2% in children and adolescents ADHD is twice as prevalent in boys The prevalence of ADHD is 2.5% in adults | Estimates vary between studies, regions, and according to study design and methods | Meta-analyses addressing the effect of bias (for example effect of study design, geographical location, and assessment tools) on prevalence are needed |

| Genetic and environmental risk factors associated with ADHD | ADHD was associated with several biological and social factors including for example genes/polygenic risk scores, maternal health in pregnancy, nutrition, repeated general anesthesia in early childhood, age at school start | Despite a huge literature on risk factors, research designs are mostly correlational rather than allowing for causal inference | Reviews of risk factors of ADHD allowing for causal inference are called for |

| Long-term prognosis and life trajectories in ADHD | ADHD was associated with school performance and school dropout, work participation, welfare dependency, smoking, drug and alcohol addiction, injuries, suicidal spectrum behavior, crime, and comorbidities, in directions as expected | The literature describes a rather bleak prognosis in ADHD, but this may be exaggerated due to the lack of adjustment for potential and residual confounding factors. The described outcomes of ADHD may thus not be causally linked to ADHD | Reviews of studies of prognosis in ADHD properly accounting for confounding are needed. The degree of confounding in this literature may also be subject of a meta-analysis, comparing adjusted and un-adjusted studies |

| ADHD and comorbidities | ADHD was associated with a high degree of comorbid somatic conditions (e.g., obesity, asthma, headache/migraine, sleep problems) and psychiatric disorders (e.g., other neurodevelopmental-, affective-, anxiety-, and eating disorders) | Studies are mostly correlational and lack data on temporality. The reviews do not sufficiently distinguish comorbidities from side-effects of medication. The causal mechanisms in the comorbidities are not addressed | Reviews addressing these limitations are needed |

| Pharmacological treatment | Stimulants were recommended as first-line medication both for children (methylphenidate preferred) and adults (amphetamine preferred) Nonstimulants were also found effective in treating ADHD in children (atomoxetine, guanfacine) and adults (atomoxetine, bupropion), though less effective than stimulants Side-effects were common and include reduced appetite, sleep problems, headache, increased heart rate and increased blood pressure | Most trials have short follow-up time (weeks and months rather than years) and focus mainly on core symptoms of ADHD as outcome There is no review evidence of pharmacological treatment effect on life-trajectory in ADHD over more than few months follow-up | Reviews of pharmacological treatment effects in ADHD on long-term prognosis with real-life outcomes including educational attainment, welfare dependency and employment, criminality, injuries, and mortality are urgently needed |

| Nonpharmacological treatment | Behavioral interventions, parental training, dietary interventions (like omega-3), and mindfulness were found to have small but positive effects in children However, the evidence for nonpharmacological treatment effects was more mixed than for pharmacological treatment Further, there are also fewer original studies and fewer reviews In adults, cognitive behavioral therapy and meditation-based therapies have shown positive effects | Most of the reviews address core ADHD symptoms and there were only few reviews that focuses on real-life outcomes and functional outcomes including for example social skills, peer relationships, school performance | Reviews of efficacy studies with outcomes beyond core ADHD symptoms are needed Reviews addressing effects of biases in this literature are needed. Biases include publication biases in favor of positive findings, the effect of nonblinded assessments should be subject for meta-analyses |

| Pharmacological versus nonpharmacological treatment in ADHD | Stimulants were superior to nonpharmacological treatment in reducing core symptoms among children and adolescents with ADHD While medications improved ADHD symptoms, psychosocial treatments were beneficial for academic and organizational skills in adolescents Pharmacological treatment was found to be cost-effective compared to nonpharmacological treatment or no treatment | Reviews compared medication with groups of different nonpharmacological intervention rather than comparing medication with one particular nonpharmacological intervention There is no review evidence of long-term effect of pharmacological versus nonpharmacological treatment on ADHD | Reviews comparing the long-term effects of pharmacological versus nonpharmacological treatment on ADHD are needed |

| Patients’ and caregivers’ experience of ADHD beyond symptoms | There was good evidence for a negative impact of ADHD on quality of life (QoL) both physically, emotionally and socially across the lifespan ADHD in children also increased parental stress. ADHD medications were chosen as a last resort and both patients and caregivers were concerned about its long-term side effects and financial costs | Although some reviews include positive aspect of having ADHD, no reviews have addressed how treatment or other interventions may influence QoL over times | Reviews assessing the impact of pharmacological or nonpharmacological interventions on QoL of patients over time are needed Reviews of qualitative studies including in-depth experiences of patients and caregivers in long-term are needed |

Narrative synthesis

Clinical guidelines and assessment (number of studies, n = 5, Table 3)

In a recent systematic review of five clinical practice guidelines, all guidelines rated stimulants as the first-line pharmacological intervention and recommended the inclusion of psychosocial intervention in the treatment [7].

A meta-analysis of sex differences in ADHD symptoms showed that boys with ADHD are more hyperactive than girls and have more difficulties in terms of motor response inhibition and cognitive flexibility [8].

For screening for ADHD in children, the Child Behavior Checklist-Attention Problem and the Conner’s Rating Scale–Revised had moderate sensitivity and specificity [9]. Conner’s Rating Scale and Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD – Symptoms and Normal-Behaviors were found as valid and time-efficient measures to assess ADHD symptoms in the classroom [10].

In adults, the Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale and the Wender Utah Rating Scale short version showed the best screening properties [11].

Prevalence of ADHD (n = 8, Table 4)

Table 4.

Prevalence of ADHD

| References | Objective | Keywords | Timeframe of database search | k | Sample size a | Analytical design | Main findings (Effect estimates, 95% CI) b | Conclusion and comments from the authors | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children and adolescents | |||||||||

| Thomas et al. [12] | Estimate worldwide prevalence of ADHD using DSM-criteria | Prevalence, DSM editions | 1977–2013 | 175 | 1,023,071 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of studies (75%) were of moderate or high quality – Pooled prevalence of ADHD was 7.2% (6.7–7.8) – In multivariate analyses, after adjusting for measurement and region, prevalence estimates for ADHD, was 2% point lower when DSM-III revised was applied as compared to DSM-IV – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 96%) were observed across analysis | Underscore that the estimated prevalence can be considered a “benchmark” – that is, deviating prevalence rates indicates over-/under diagnosis | High (8/9) |

| Ayano et al. [13] | Assess the prevalence of ADHD in Africa | Prevalence, Africa | Database inception – (not mentioned last date of search) | 12 | 11,465 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of studies were of high quality – Pooled prevalence of ADHD was 7.47% (6.0–9.26), with a greater prevalence among boys than girls – The prevalence rate was highest for predominantly inattentive subtype (ADHD-I) in both boys (4.05%, 3.11–5.27) and girls (2.21%, 1.61–3.03) – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 90%) were observed across analyses | Reasons for gender differences in ADHD needs to be explored | High (8/9) |

| Wang et al. [14] | Identify the prevalence of ADHD in China | Prevalence, China | Database inception – March 2016 | 67 | 275,502 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of studies were of moderate quality – The prevalence rate of ADHD was 6.26% (5.36–7.22), with ADHD-I being the most common subtype – Prevalence rate varied between studies due to “geographical location” and “information sources” differences – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 95%) were observed across analyses | Estimated prevalence provides a “benchmark” to evaluate the disease burden of ADHD in China. However, a nation-wide research is needed to identify more “accurate estimate” | High (8/9) |

| Cénat et al. [15] | Estimate prevalence of ADHD among US Black individuals | Prevalence, US Black individuals | Database inception – October 2019 | 21 | 154,818 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate to high quality – Overall prevalence of ADHD was 14.5% (10.6–19.6), for individuals less than 18 years 13.9% (9.6–19.6) – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 = 99.7% were observed across analyses | Assessment and monitoring of ADHD among black individuals needs to be increased and research on ADHD prevalence across different ethnic groups in other western countries are needed | High (8/9) |

| Shooshtari et al. [16] | Provide an up to date prevalence of ADHD in Iran | Prevalence, Iran | January 1990–December 2018 | 36 | 33,621 children, adolescents, and adults | Narrative synthesis | – Prevalence estimates varied substantially across the studies and provided a range of heterogeneous data – Total prevalence of ADHD ranged between 11.0–25.8% among pre-school children; between 3.1–17.3% among school children, and between 3.9–25.1% among adults | Comparing prevalence estimates across studies was difficult due to differences in assessment methods and samples. Therefore, prevalence studies need to apply well-defined diagnostic criteria | Moderate (7/9) |

| Kazda et al. [17] | Systematically evaluate, and synthesize the evidence on overdiagnosis of ADHD in children and adolescents utilizing published 5-question framework for detecting over diagnosis in noncancer conditions | Overdiagnosis | 1979–August 2020 | 334 | Not given | Narrative Synthesis | – One-third of the studies were of high quality – Substantial evidence of a reservoir of ADHD was reported by 104 studies, which suggest that number of diagnosis could increase in future – 45 studies provided an evidence that the actual ADHD diagnosis had increased – 25 studies reported that these additional cases may be on the milder end of the ADHD spectrum, and – 83 studies suggested that pharmacological treatment of ADHD was increasing | High quality studies are needed to identify the long-term benefits and harms of diagnosing and treating ADHD in young people with milder symptoms | Moderate (7/9) |

| Adults | |||||||||

| Song et al. [18] | Assess the global prevalence of adult ADHD in the general population | Prevalence, Worldwide | January 2000–December 2019 | 40 | 107,282 for persistent adult ADHD and 50,098 for symptomatic adult ADHD | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of studies were of moderate to high quality – Based on data published from 2005 to 2019, the pooled prevalence was 4.61% (3.41–5.99) and 8.83% (7.23–10.57) for persistent and symptomatic adult ADHD respectively – The most common age group for adult ADHD cases was 18–24 – LMICs showed a higher prevalence of persistent adult ADHD than HICs, while WHO regions showed different rates of symptomatic adult ADHD – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 97%) were observed across analyses | To better understand the global epidemiology of both persistent and symptomatic adult ADHD, there is still a need for well-defined diagnostic procedures and more large-scale international studies with minimal methodological heterogeneity | High (9/9) |

| Dobrosavljevic et al. [19] | Assess ADHD prevalence among older adults ≥50 according to different assessment methods | Prevalence, Older adults | Database inception – June 2020 | 20 | 20,999,871 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate quality – The prevalence of ADHD was higher 2.18% (1.51–3.16) for validated scales in community sample compared to the prevalence assessed based on clinical diagnosis 0.23% (0.12–0.43), and treatment 0.09% (0.06–0.15) – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 87%) were observed across analyses | Prevalence studies in community samples should use more comprehensive assessment tools to explore whether individuals with elevated ADHD symptoms meet established diagnostic criteria. They should examine the possible reasons behind high levels of ADHD symptoms reported via validated scales | Moderate (7/9) |

Abbreviations: DSM, diagnostic statistic model; HICs, high-income countries; k, total number of primary studies included; LMICs, lower and middle-income countries; WHO, World Health Organization.

a

Total participants included in the systematic review and meta-analysis or otherwise specified.

b

For findings from meta-analysis, if given effect estimates with 95% CI are presented or otherwise specified.

Prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents

The prevalence of ADHD among children and adolescents was assessed in four different meta-analyses [12–15] and one systematic review [16]. Internationally, the pooled prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents was estimated to be 7.2% (95% CI: 6.7–7.8) in a meta-analysis of 175 studies including more than 1 million participants [12]. Most of the included studies were conducted within school populations (74%), and few used a whole-population approach (10%). In a multi-variable analysis, the prevalence estimate was 2 percentage points lower in studies conducted in Europe compared to North America after adjusting for the edition of diagnostic manual and measurement tools which included clinical interviews, symptom-only criteria, and reports of ADHD diagnosis [12]. Further, a meta-analysis of prevalence studies from Africa reported a pooled prevalence of 7.47% (6.0–9.26). As expected, gender differences were found with a male: female ratio of 2.0:1.0 [13]. The prevalence in China was 6.26% (5.36–7.22) [14], while it was 13.87% (9.59–19.64) among black individuals in the USA [15]. All included reviews reported that significant heterogeneity in the prevalence attributed to the source of study population, geographical location, and source of data was found across included studies.

A systematic review found substantial evidence of overdiagnosis of ADHD. The authors reported that ADHD diagnoses have consistently increased between 1989 and 2017, and that the majority of new cases were on the milder end of the ADHD spectrum [17].

Prevalence of ADHD in adults

The worldwide pooled prevalence among adults was 4.61% for persistent adult ADHD and 8.83% for symptomatic adult ADHD [18]. By adjusting for the “global demographic structure,” the prevalence of persistent adult ADHD was 2.58% (95% CI:1.51–4.45) and symptomatic adult ADHD 6.76% (4.31–10.61), translating to 139.84 and 366.33 million affected adults in 2020 globally. The meta-analysis found that the prevalence of ADHD decreased with age [18]. The prevalence among adults aged ≥50 was 2.2% based on validated scales applied in the general population, and 0.2% when based on clinical diagnosis [19].

Genetic and environmental risk factors associated with ADHD (n = 41, Table 5)

Table 5.

Genetics and environmental risk factors associated with ADHD

| References | Objective | Keywords | Timeframe of database search | k | Sample size a | Analytical design | Main findings (Effect estimates, 95% CI) b | Conclusion and comments from the authors | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ronald et al. [20] | Review if ADHD polygenic risk score is associated with ADHD and related traits | Genetics, Polygenic risk score | Not given | 44 | >14,000 | Narrative synthesis | – Majority (80%) of included studies were of high quality – Strong evidence was found for the of associations between ADHD PRS and ADHD, ADHD traits, brain structure, education, externalizing behaviors, neuropsychological constructs, physical health, and socioeconomic status – PRS associated with ADHD had an OR of 1.22 to 1.76%; variance explained in dimensional assessments of ADHD traits ranged from 0.7 to 3.3% | The review suggest that the ADHD PRS is robust and reliable, associating not only with ADHD but many outcomes and challenges known to be linked to ADHD | High (8/9) |

| Prenatal factors | |||||||||

| Li et al. [21] | Clarify the association between maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity and risk of ADHD in offspring | Obesity, Confounding | 1975–2018 | 14 (8 in meta-analysis) | 784, 804 mother–child pairs | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate to high quality – Maternal overweight (RR = 1.31,1.25–1.38) and obesity (RR = 1.92, 1.84–2.00) both increased the risk of ADHD in offspring – However, the association was significantly attributable to unmeasured familial confounding and was not a causal – No significant heterogeneity were observed across analysis | Future studies using robust methodological design that considers unmeasured familial confounders, and genetic and environmental origin of such confounders and includes various populations are required | High (8/9) |

| Ai et al. [22] | Assess the association between antibiotic exposure and the risk of ADHD in childhood | Antibiotic ADHD, Microbiome | Database inception – January 2021 | 11 | 2,238,348 | Random effects meta-analysis | Included studies were of moderate to high quality – Maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of ADHD in offsprings (OR = 1.14; 1.10–1.18) – The included studies had insufficient adjustment for confounders – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 = 64%) was observed across analysis | Future research should examine whether different types, courses, and durations of antibiotic use affect ADHD risk and adjust for potential confounders | Moderate (7/9) |

| Gou et al. [23] | Evaluate the association between maternal acetaminophen use during pregnancy and the risk of ADHD in children | Acetaminophen, Pregnancy | Database inception – November 2018 | 8 | 244,940 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – There was an association between maternal acetaminophen use during pregnancy and the risk of ADHD in offspring (Rrat = 1.25, 1.17–1.34) with a greater risk among offspring who were exposed to acetaminophen at the third trimester and for longer duration, that is, 28 days or more – No significant heterogeneity were observed across analyses | Caution must be taken while interpreting the result as this observed association might be due to potentially unidentified or inadequately controlled confounders. Hence, further studies are required | Moderate (7/9) |

| Man et al. [24] | Assess the association between antidepressant exposure during pregnancy and ADHD in offspring | Antidepressant, Pregnancy | January 1946–July 2017 | 8 | 2,886,502 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of high quality – Increased risk of ADHD among those with prenatal exposure to antidepressants compared to nonexposure was observed (Rrat = 1.39, 1.21–1.64) – However, the meta-analysis result of three studies that used sibling-matched analyses yielded a nonsignificant association – No significant heterogeneity were observed across analyses | Association between prenatal antidepressants exposure and ADHD in children is likely to be confounded by other factors | High (9/9) |

| Dan et al. [25] | Assess the relationship between maternal pregestational or gestational diabetes and occurrence of ADHD in children | Maternal diabetes, ADHD, offspring | Database inception – January 2019 | 7 | 3,169,529 out of which, 148,374 children exposed to maternal diabetes, and 3,021,155 belonging to the reference | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of the studies were of moderate quality – Maternal pregestational diabetes increased the risk of ADHD in offspring by 44% (1.32–1.57) with no significant heterogeneity – -However, no association was observed between gestational diabetes and ADHD (RR = 1.19, 0.99–1.42) with moderate heterogeneity (I 2 = 68.7%) | Given the limited availability of reliable information, further cohort studies are required to assess this relationship more comprehensively | Moderate (7/9) |

| Rowland et al. [26] | Explore the association between gestational diabetes and ADHD | Pregnancy, Gestational diabetes | Database inception – April 2021 | 15 | Children of 132,458 mothers with gestational diabetes, 857,623 control. 401 children with ADHD, 1,828 controls | Random effects meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of poor quality – No significant difference was observed between children of mothers with gestational diabetes and controls – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 > 45%) was observed across analysis | Not mention for ADHD | High (9/9) |

| Dong et al. [27] | Assess the association between prenatal exposure to MSDP and ADHD in offspring | Prenatal exposure, Maternal smoking during pregnancy | Database inception – June 2017 | 27 | 3,076,173 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of high quality – Significant association was observed between prenatal exposure to MSDP or maternal smoking cessation during the first trimester and ADHD in offspring, while there was no such association for maternal smoking cessation before pregnancy – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 80%) was observed across analysis for MSDP | More studies with robust designs, more effective exposure assessment, and large sample size are needed to clarify the causal relationship between MSDP and ADHD in offspring | High (8/9) |

| Schwartz et al. [28] | Determine the association between POE and ADHD symptoms in children and adolescents | Prenatal opioid exposure | January 1950–October 2019 | 7 | 319 children with POE and 1,308 nonexposed children | Random-effect meta-analysis | – POE was associated with higher rates of hyperactivity (SMD:1.4, 0.49–2.31), inattention (SMD: 1.35, 0.69–2.01) and combined ADHD symptoms scores (SMD: 1.27, 0.79–1.75) – POE was associated with ADHD symptoms both at preschool and school age – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 87%) were observed across analyses | Future research should clarify the relationship between biological, environmental, and social risk factors, respectively, and ADHD symptoms in children with POE | Moderate (7/9) |

| Qu et al. [29] | Explore the relationship between maternal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and early ADHD in children | Perfluoroalkyl substances, Maternal exposure | Database inception – October 2020 | 15 (9 in meta-analysis | 17,565 | Narrative synthesis and random effects meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – No statistical significant differences was found for early ADHD and exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances (perfluorooctanoic acidperfluorooctane sulfonate, perfluorohexane sulfonate, perfluorononanoic acid, perfluorodecanoic acid) – Subgroup analysis showed a positive association between PFOS concentration in children’s blood and early ADHD (OR = 1.05, 1.02–1.08) – Subgroup analysis showed a positive association between perfluorononanoic acid level in maternal blood and ADHD in children (OR = 1.42, 1.04–1.81) – Subgroup analysis showed a positive association between perfluorooctane sulfonate level and ADHD in children in America (OR = 1.05, 1.02–1.08 – Moderate to significant (I 2 > 54.7–87.2) heterogeneity were observed across analyses before subgroup analysis | To better understand the pathogenesis of ADHD, epidemiological studies are needed in several regions, particularly on PFAS exposure types | Moderate (7/9) |

| Perinatal factors | |||||||||

| Zhu et al. [30] | Evaluate the association between perinatal hypoxic–ischemic conditions and future ADHD | Hypoxia, ischemia, Risk factor | Database inception – before September 2015 | 10 | Cases: 45,821 Controls: 9 2,07,363 | Fixed or random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate quality – Perinatal hypoxic–ischemic conditions like preeclampsia (OR = 1.31, 1.26–1.37), Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes (OR = 1.31,1.12–1.54), breech/transverse presentations (OR = 1.14,1.06–1.23), and prolapsed nuchal cord (OR = 1.10,1.06 – 1.15) were all associated with increased risk of future ADHD – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 = 63%) was observed for analysis of Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | Given the limited number of studies, more well-designed studies are needed to confirm this association | High (8/9) |

| Franz et al. [31] | Determine the association between preterm and LBW and future ADHD, both for categorical diagnosis and dimensional symptomatology, compared with controls | Very Preterm, Very Low Birth Weight, Extreme Preterm, Extreme Low Birth Weight | Database inception – 2017 | 34 | 5,291 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate quality – VP/VLBW and EP/ELBW individuals were at an increased risk of a categorical diagnosis of ADHD with highest OR for the most extreme cases – This was supported by a meta-analysis based on ADHD symptomatology showing a significant association for VP/VLBW and symptoms of inattention (SMD = 1.31,0.66–1.96), hyperactivity and impulsivity (SMD = 0.74, 0.35–1.13), and combined (SMD = 0.55, 0.42–0.68) as compared to controls – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 90%) was observed across analysis except for the combined dimension in the VP/VLBW group (moderate I 2 = 54%) | Specific causal determinants associated with prematurity and LBW and subsequent ADHD needs to be studied | High (9/9) |

| Serati et al. [32] | Review the literature on obstetric and neonatal complications and future risk of ADHD | Perinatal complications, Child development | Database inception – December 2016 | 40 | 57–1,772,548 per study | Narrative synthesis | – Majority of included studies were of moderate quality – LBW (Cohen’s d effect size range = 0.31–1.64) and preterm birth (range d = 0.41–0.68) were identified as an important risk factors for future ADHD | PB and LBW children should be carefully monitored for an early diagnosis of ADHD | Moderate (6/9) |

| Curran et al. [33] | Investigate the impact of CS compared to vaginal delivery and the odds of subsequent ADHD in children | ADHD, Cesarean section | Database inception – February 2014 | 4 | Not given | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of poor to moderate quality – Unadjusted estimates showed a positive association between CS and ADHD in offspring – However, the only two studies reporting adjusted risk estimates showed that this relation was not significant (OR = 1.07,0.86–1.33) – No heterogeneity were observed across analyses | Included studies were unable to provide a clear description of the possible association. Hence, future studies need to adjust for potential key confounders and effect modifiers (type of CS, sex of the child, maternal obesity, socioeconomic status, maternal age) to assess the relationship between CS delivery and ADHD | Moderate (7/9) |

| Xu et al. [34] | Examine the association between CS and ADHD in children | ADHD, Cesarean section, Confounders | Database inception – December 2018 | 9 | More than 2.5 million | Fixed or random‐effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of high quality – CS was associated with a small increase in the later risk of ADHD in offspring (OR = 1.14, 1.11–1.17) – However, the meta-analysis result of data from sibling analyses showed the association as marginally significant (OR = 1.06, 1.00–1.13), suggesting the association was due to confounders – No heterogeneity were observed across analyses | The observed association may have been overestimated as the included primary studies could not control for important confounding factors. Hence, more prospective cohort studies with large sample size and data on potential confounders/predictors are required | High (8/9) |

| Min et al. [35] | Explore the association between parental age at delivery and ADHD risk in offspring | Parental age; Children | Database inception – April 2021 | 11 | Cases: 111,101 Controls: 4,306,047 | Random effects meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of moderate quality – Compared with the reference groups, the lowest parental age category was associated with an increased risk of ADHD in the offspring (OR = 1.49, 1.19–1.87) and (OR = 1.75,1.31–2.36) for mother and father, respectively – No significant association was found between the highest parental age and ADHD – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 95%) were observed across analyses | A causal relationship and mechanisms between parental age and the risk of ADHD in offspring need to be explored in future research | High(8/9) |

| Postnatal factors | |||||||||

| Tseng et al. [36] | Examine the relationship between breastfeeding and ADHD in children, taking into account of important factors such as the duration and methods | Breastfeeding, Nutrition, Risk | Database inception – September 2017 | 11 | Cases: 4,107 Controls: 90,392 | Random effects meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of moderate quality – Children with ADHD had significantly less breastfeeding duration than controls (Hedges’ g = −0.36, −0.61 to –0.11) – Association was found between nonbreastfeeding and ADHD children (ajOR = 3.71, 1.94–7.11) – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 = 42.5%) was observed across analysis | Additional longitudinal studies are needed to confirm/refute the association and to explore possible mechanisms underlying this association | Moderate (7/9) |

| Zeng et al. [37] | Investigate the association between maternal breastfeeding and ADHD in offspring | Breastfeeding, Nutrition, Protective factor | Unclear | 12 | ADHD Cases: 3,686 Controls: 106,907 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of moderate quality – Maternal breastfeeding (of any duration) may reduce the risk of future ADHD in children (OR = 0.70, 0.52–0.93) compared to those who were never breastfed – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 > 70%) was observed across analysis | Prospective studies should adjust for potential confounders and apply standardized diagnostic methods to examine the causal relationship | Moderate (6/9) |

| Huang et al. [38] | Explore the association between postnatal exposure to SHS and future risk of ADHD | Second-hand smoking, Postnatal | Database inception – January 2020 | 9 | ADHD cases: 6,663 Controls: 93,825 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – Children exposed to SHS were found to be at the increased risk of ADHD (OR = 1.60, 1.37–1.87) – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 = 42.5%) was observed across analysis | Causal relationship between SHS and ADHD needs to be determined by fully adjusting for potential confounders | Moderate (7/9) |

| Environmental factors | |||||||||

| Asarnow et al. [39] | Investigate ADHD diagnoses in children and adolescents following concussions and mild, moderate, or severe TBI | Injury, Traumatic Brain Injury | 1981–December 2019 | 24 | TBI cases: 12,374 Controls: 43,491 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of moderate quality – Children with TBI were at increased risk of getting ADHD compared with those with other injuries (1 year: OR = 4.81,CrI: 1.66–11.03) and (>1 year OR = 6.70,2.02–16.82) and noninjured controls (1 year OR = 2.6, 0.7–6.6), and (>1 year OR = 6.25, 2.06–15.04), as well as those with mild TBI (1 year OR = 5.69,1.46–15.67), (>1 year OR: 6.65, 2.14–16.44) – Of 5, 920 children with severe TBI, 35.5% had ADHD more than 1 year postinjury | Further studies with large sample size particularly for concussion and other injuries are needed | Moderate (6/9) |

| Sun et al. [40] | Examine the evidence for a relationship between general anesthesia induced in childhood and the risk of ADHD | Attention, Behavior, Cognitive, Surgery, Anesthesia | Database inception – October 2020 | 7 | ADHD cases: 49,141 Controls: 251, 246 | Random effects meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – Exposure to general anesthesia in childhood was associated with a risk of ADHD in later life (RR = 1.24,1.11–1.38) – Subgroup analysis showed that a single anesthetic exposure was not associated with risk for ADHD – Two or more exposures was associated with risk for ADHD – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 = 74.8%) was observed for two or more exposure | To confirm these findings, more prospective cohort studies with larger sample sizes are needed | High (9/9) |

| Daneshparvar et al. [41] | Review relevant literature related to lead exposure and ADHD symptoms in children | Blood Lead Level, Lead Poisoning | Database inception – May 2014 | 18 | 12,195 | Narrative synthesis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – Blood lead level of < 10 g/dL have a significant effect on at least one ADHD subtype | Recommends revising the present threshold (less than 10 g/dL) for permissive blood levels and measuring the BLL in children to reduce the harm caused by prolonged exposure to lead | Moderate (6/9) |

| Kalantary et al. [42] | Examine the association between ADHD symptoms and exposure to PAH exposure during the prenatal and postnatal periods in children of nonsmoking mothers | PAHs, Children | Database inception – September 2018 | 6 | 2,799 | Fixed and random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – Although four of six studies (all by the same author) found a significant association between PAH exposure and later ADHD, no association was observed between prenatal and postnatal exposure to PAH and future ADHD in children when including adjusted analyses from all the six included studies (OR = 1.99,0.96–4.11) – No heterogeneity was observed across analysis | Additional research needs to be conducted in different countries | Moderate (7/9) |

| Zhang et al. [43] | Determine the association between exposure to air pollutants and development of ADHD in children | PAHs, Nox, Particulate matter | Unclear | 9 | >98,000 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – No significant association was found between exposure to PAHs (RR = 0.98, 0.82–1.17), NOx (RR = 1.04, 0.94–1.15, and PM (RR = 1.11, 0.93–1.33) and an increased risk of ADHD in children – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 = 60.1%) was observed NOx and PM | Further prospective studies to determine causal relationship between exposure to particles and ADHD are needed | High (8/9) |

| Aghaei et al. [44] | Synthesize relationship between exposure to air pollutants and risk of ADHD in children | Ambient air pollutants, particulate matter, ADHD | Database inception – 2018 | 28 | 140,159 | Narrative synthesis | – Due to the significant variation in methodology used in included studies, no firm conclusion can be drawn about the exposure to ambient gaseous and particulate matters and the risk of ADHD in children | Further studies need to apply accurate exposure and outcome assessment method and consider all possible confounders | High (8/9) |

| Lam et al. [45] | Assess association between developmental exposure to PBDE and ADHD | Polybrominated diphenyl ether, ADHD | Database inception – September 2016 | 9 | 62–622 mother–child pairs | Narrative synthesis | – Due to limited data, no firm conclusion can be drawn about the exposure to PBDE and the risk of ADHD in children | Further studies of good quality are needed | High (9/9) |

| Caye et al. [46] | Determine the relationship between age and ADHD diagnosis | Relative age, Immaturity | Database inception – December 2018 | 25 | 8,076,570 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of the included studies were of high quality – Children born in the last 4 months of the school calendar year were at higher risk of receiving ADHD diagnosis compared to their relatively older class peers (RR = 1.34,1.26–1.43) – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 = 96.7%) was observed across analysis | Relative maturity and developmental age should be consistently considered while making an ADHD diagnosis | High (9/9) |

| Russell et al. [47] | Assess the association between SES and ADHD | Socioeconomic status, Health inequalities | 1999–2013 | 42 | 53 to 842 per study | Random-effect meta-analysis | – The association between socioeconomic disadvantage and ADHD was a consistent finding, but can be mediated by parental mental health, maternal smoking during pregnancy, or other risk factors that are more prevalent in families with low SES | Further research that considers possible mechanism between SES and ADHD is warranted | Moderate (7/9) |

| Langevin et al. [48] | Disentangle the association between CSA and ADHD | Child sexual abuse, Predictor | Database inception – January 2020 | 28 | 75,306 | Narrative synthesis | – Variation in quality of included studies and lack of longitudinal studies restricted from untangling the association between CSA and ADHD | Rigorous longitudinal studies including those that assess the confounding role of other maltreatment forms and trauma-related symptoms are needed | Moderate (7/9) |

| Del-Ponte et al. [49] | Examine the association between dietary patterns and ADHD | Diet, Dietary pattern | Unclear | 14 | 375–16,831 participants per study | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of moderate quality – Children and adolescents consuming healthy diets have lower odds of having ADHD (OR = 0.65, 0.44–0.97) compared to those consuming unhealthy diet (OR = 1.41, 1.15–1.74) – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 > 73%) were observed across analysis | Longitudinal studies are needed to strengthen the evidence about the relationship between diet and ADHD | Moderate (6/9) |

| Farsad-Naeimi et al. [50] | Determine relationship between sugar consumption and the development of ADHD symptoms | Sugar, Soft drink | Database inception – March 2020 | 7 | 25,945 | Fixed- and random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – A positive relationship was found between sugar and soft drink consumption and ADHD (d = 1.27, 1.02–1.42) – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 = 81.9%) was observed across analysis | Longitudinal studies that examine a potential causal relationship between sugar and soft drink consumption, and ADHD are needed | High (8/9) |

| Khashbakht et al. [51] | Synthesize the available literature on the relation between vitamin D status and ADHD | Vitamin D, Children, Adolescents | Database inception – June 2017 | 13 | Cases: 33–1,331 Controls: 20–6,492; Cohort:3,733 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of moderate quality – Children and adolescents with ADHD had a lower mean concentration of serum 25 (OH)D than healthy controls – The studies which reported ORs also showed a significant association between lower vitamin D status and ADHD (OR = 2.57; 1.09–6.04) – Further, a meta-analysis from prospective studies also showed an inverse relationship between perinatal vitamin D and ADHD (RR = 1.40, 1.09–1.81) – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 80%) was observed across analysis | To understand the causal association between vitamin D status and the risk of developing ADHD, prospective cohort studies with large sample size, including different population and even population-based intervention studies that consider the maximum number of possible confounders should be conducted | High (8/9) |

| La Chance et al. [52] | Estimate the relationship between blood ratio of Omega-6 and Omega-3 fatty acids (n6/n3) and AA/EPA, to ADHD symptoms | Omega-3 fatty acids, Omega-6 fatty acids | Database inception – April 2014 | 5 | Not given | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of high quality – Children and youth with ADHD have higher n6/n3 fatty acid ratios (SMD = 1.97,0.90–3.0)4, and higher AA/EPA ratios (SMD = 8.25,5.94–10.56) than those in controls – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 = 83%) was observed for n6/n3 fatty acid ratios | Future research could assess whether fatty acid ratios could be used as biomarkers to identify which children with ADHD who may specifically benefit from treatment with essential fatty acids to normalize the n6/n3 or AA/EPA ratios | High (8/9) |

| Huang et al. [53] | Determine the relationship between magnesium level and ADHD in children | Magnesium, Trace element, Nutrition | Database inception – October 2018 | 12 | Cases: 2,872 Controls: 2,838 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of high quality – ADHD children have significantly lower peripheral blood magnesium level (Hedges’ g = −0.5,−0.8 to −0.2) and lower hair magnesium levels (Hedges’ g = −0.7,−1.3 to −0.1) compared to controls – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 = 85%) was observed for hair magnesium levels | Prospective studies with a large sample size are required to determine the causal relationship between magnesium level and the pathophysiology of ADHD | High (8/9) |

| Effatpanah et al. [54] | Examine the relationship between magnesium status and ADHD | Magnesium, Trace element | Database inception – August 2018 | 7 | Cases: 9–1,331 Controls: 11–1,331 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate quality – Children and adolescents with ADHD have 0.10 mmol/l (−0.18−0.02) lower serum magnesium levels than controls indicating an inverse relationship between magnesium level and ADHD – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 95%) was observed across analysis | Further observational studies using standard diagnostic measurement are required to draw meaningful conclusions about magnesium level and ADHD | High (9/9) |

| Shih et al. [55] | Assess the association between peripheral manganese level and ADHD | Manganese, Pediatric psychiatry | Database inception – March 2018 | 4 | Cases: 175 Controls: 999 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate quality – Meta-analysis found significantly higher peripheral manganese levels in ADHD children compared to controls when including studies with either blood or hair levels) (Hedges’ g = 0.30,0.02–0.58) – However, the association was no longer significant when only blood manganese level was analyzed separately (Hedges’ g = 0.32, −0.03 − 0.69) – Moderate heterogeneity (I 2 > 50%) was observed across analysis | Additional primary studies are warranted to understand better the relationship between peripheral manganese level and ADHD | Moderate (7/9) |

| Degremont et al. [56] | Examine whether children with ADHD have lower serum and brain iron concentrations, compared with healthy control subjects | Brain iron, Serum iron, Iron status, Serum ferritin | 2000–June 2019 | 20 | Cases: 2,209 Controls: 2,982 | Narrative synthesis | – Majority of included studies were of moderate quality – Serum ferritin concentrations varied between studies, with 10 of 18 studies finding higher concentration in patients with ADHD compared to healthy controls – For serum iron, 7 of 10 studies showed no difference, 2 studies showed lower concentrations in patients with ADHD, and 1 study showed higher concentration. – 3 studies reported lower brain iron in patients with ADHD – Study methods and participants were heterogeneous | There is need for longitudinal studies and larger MRI studies using magnetic field correlation to measure brain iron concentration in different regions of the brain | Moderate (7/9) |

| Cortese et al. [57] | Summarize the evidence about iron level and ADHD | Iron, Ferritin, Trace element | Database inception – July 2012 | 22 | 500–2,000 | Narrative synthesis | – Most of the studies assessing iron status in children with ADHD used serum ferritin as a measure, with mixed findings (i.e., both significant and nonsignificant associations) | More research based on other measures for assessment than serum ferritin are required to elucidate the relationship between iron status and ADHD | Moderate (7/9) |

| Tseng et al. [58] | Identify the association between iron status and ADHD | Iron, Ferritin | Database inception – August 2017 | 17 | >10,000 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – Children with ADHD have lower peripheral serum ferritin levels (Hedges’ g = −0.24,−0.44 to −0.05), but not iron or transferrin levels compared to healthy controls – Children with iron deficiency have more severe ADHD symptoms than ADHD children without ID (Hedges’ g = 0.88, 0.32–1.45) – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 = 82.9%) was observed for peripheral serum ferritin level | Prospective studies are required to provide better insight into the relationships between iron status and ADHD symptoms and to clarify the potential pathophysiological mechanisms | High (8/9) |

| Ghoreisy et al. [59] | Estimate the association between hair and serum/plasma zinc levels and ADHD | Zinc, Trace elements | Database inception – October 2020 | 22 | Cases: 1,280 Controls: 1,200 | Random effects meta-analysis | – Majority of included studies were of high quality – Serum or plasma zinc levels in subjects with ADHD were not statistically different compared to controls (WMD = − 1.26 μmol/L,−3.72–1.20) – After removing one study which showed a significant higher levels of serum/plasma zinc in subjects with ADHD compared to the controls, zinc levels were lower in ADHD patients (WMD = − 2.49 μmol/L,−4.29 to −0.69) – Further, hair zinc levels in cases with ADHD were not statistically different compared to controls (WMD: − 24.19 μg/g; −61.80 – 13.42) – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 98%) were observed across analyses | Further well-designed studies are needed to clarify the role of zinc in the etiology of ADHD | High (8/9) |

| Luo et al. [60] | Explore the available evidence on the correlation between zinc and ADHD | Zinc, ADHD | Database inception – April 2019 | 11 | 1,517 | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Majority of the included studies were of good quality – No significant difference in zinc level in blood (SMD = −0.91,−1.88–0.07) or hair (SMD = 1.4,−4.49–7.33) was found between children and adolescents with and without ADHD – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 > 95%) were observed across analysis | Additional studies with a large sample size and robust methodology are required | Moderate (7/9) |

Abbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; CrI, credible interval; CS, cesarean section; CSA, child sexual abuse; d, effect size; EA, eicosapentaenoic acid; ID, iron deficiency; k, total number of included studies; MSDP, maternal smoking during pregnancy; Nox, nitrogen oxides; OR, odds ratio; PAH, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon; PB, preterm birth; PBDE, polybrominated diphenyl ether; PM, particulate matter; POE, prenatal opioid exposure; RR, relative risk; Rrat, risk ratio; SES, socioeconomic status; SHS, second-hand smoke; SMD, standardized mean difference; TBI, traumatic brain injury; VLBW/ELBW, very/extreme low birth weight; VP/EP, very and extreme preterm; WMD, weighted mean difference.

a

Total participants included in the systematic review and meta-analysis or otherwise specified.

b

For findings from meta-analysis, if given effect estimates with 95% CI are presented or otherwise specified.

In this section, we use terms like risk, correlation, protective, and association according to reports in the systematic reviews, without indicating causality. Generally, this literature did not bring evidence for conclusions on causality, which will be discussed later.

Genetic factors

One systematic review found strong evidence that the common genetic variants underlying ADHD, as measured by the ADHD polygenic risk score, were associated not only with diagnosed ADHD but also with more dimensional ADHD traits [20].

Maternal factors

Maternal pre-pregnancy overweight [21], use of antibiotics [22], acetaminophen [23], and antidepressants [24] during pregnancy, and maternal pregestational diabetes [25], but not gestational diabetes [26], were associated with increased rates of ADHD in offspring. However, the authors stated that associations may be due to unmeasured confounding and thus not causal (e.g., the association with maternal overweight was explained by familial confounding). Maternal smoking during pregnancy (odds ratio (OR) = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.41–1.72) or smoking cessation during the first trimester was associated with ADHD in offspring [27]. Similarly, prenatal opioid exposure was associated with higher ADHD symptom scores (standardized mean difference (SMD) =1.27, 0.79–1.75) [28]. Maternal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances was not associated with ADHD in their children [29].

Perinatal complications like maternal preeclampsia [30], very preterm birth/very low birth weight (OR = 3.04, 95% CI: 2.19–4.21) [31], or low birth weight [32] were associated with offspring ADHD. Likewise, the caesarian section was reported to be associated with later ADHD diagnosis in unadjusted analyses [33], but a later review reported this association to be partly or entirely accounted for by residual confounding [34].

A nonlinear relation between parental age and risk for ADHD in the offspring was found with the highest risk for parents below 20 years and lowest risk for parents in the mid-thirties [35].

While maternal breastfeeding was associated with a reduced risk of ADHD in children [36, 37], postnatal exposure to second-hand smoking was associated with increased risk (OR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.30–1.80) [38].

Compared to children with other injuries or without injuries, children with severe traumatic brain injuries had an increased risk of being diagnosed with ADHD at less or more than 1 year, respectively, after the injuries [39]. Likewise, two or more exposures to general anesthesia were associated with an increased risk of ADHD in later life (relative risk RR = 1.84, 1.14–2.97) [40]. Blood lead level was associated with higher ADHD rates in children and adolescents [41]. No significant association was found between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure and ADHD in children [42, 43], and there were inconclusive evidence for an association between exposure to air pollution [44] or polybrominated diphenyl ethers [45] and ADHD.

According to two included reviews, children being relatively younger than classmates had higher rates of ADHD diagnosis [17, 46], with one reporting the relative risk of 1.34 (95% CI: 1.26–1.43) for the youngest children [46]. Further, two reviews suggested an association between socioeconomic disadvantage and risk of ADHD [15, 47], with one suggesting it to be mediated by factors such as parental mental health and maternal smoking during pregnancy [47]. The evidence regarding child sexual abuse as a predictor for ADHD was unclear [48].

Dietary pattern, nutrition, and trace elements

Children and adolescents consuming healthy diet had lower risk of having ADHD compared to those consuming unhealthy diet [49]. Positive relationship was indicated between total sugar intake from soft drinks and dietary sources and ADHD symptoms in children and adolescents [50]. Other nutritional factors associated with higher rates of ADHD among children and adolescents were low serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, lower perinatal and childhood vitamin D status [51], elevated ratios of both blood omega-6 to omega-3 and arachidonic acid to eicosapentaenoic acid fatty acids [52]. Two systematic reviews reported significantly lower serum manganese levels in children with ADHD [53, 54]. Another review revealed higher peripheral manganese levels in both blood and hair in children and adolescents with ADHD compared to healthy controls [55].

A review from 2021 suggested that brain iron concentrations, specifically in the thalamus, were lower in children with ADHD than in healthy controls [56]. However, mixed results were reported for systemic iron level [56, 57]. In contrast, a review from 2018 concluded that low serum iron levels were associated with ADHD [58]. There was no difference in zinc levels in blood, serum, plasma [59] or hair between children and adolescents with ADHD and healthy controls [60].

Long-term prognosis and life trajectories in ADHD (n = 19, Table 6)

Table 6.

Long-term prognosis and life-trajectories in ADHD

| References | Objective | Keywords | Timeframe of database search | k | Sample size a | Analytical design | Main findings (Effect estimates; 95% CI) b | Conclusion and comments from the authors | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christiansen et al. [61] | Synthesize evidence of an association between ADHD diagnosis in childhood and later education, earnings and employment, compared to children without an ADHD diagnosis | Life-course, Occupation, Work, Employment | Database inception – November 2020 | 6 | Cases: 1,380 Controls: 888 | Narrative synthesis | – Majority of the included studies were of moderate quality-ADHD was associated with lower quality employment, lower lifetime income, and more part time and unskilled work and with lower educational attainment measured in several ways | There is a need for further high-quality research evaluating factors and interventions that reduce the long-term vocational impacts of childhood ADHD, especially ADD, which is not addressed in the present literature | High (9/9) |

| Erskine et al. [62] | Explore the potential outcomes associated with ADHD diagnosis | ADHD, Long-term prognosis | 1980–March 2015 | 101 | 71 to slightly less than 2 million | Random-effect meta-analysis | – Included studies were of moderate to high quality – ADHD was associated with a range of negative life outcomes, including failure to complete high school (OR = 3.70, 1.96–6.99), use of education services (OR = 6.37, 2.58–15.73), dismissal from work (OR = 3.92, 2.68–5.74), substance dependence (OR = 2.45,1.44–4.17), violence – related arrest (OR = 3.63, 2.31–5.70) – Significant heterogeneity (I 2 = 83.1%) was observed for substance dependence | A better comprehension of the underlying mechanism for the association between ADHD and several long-term outcomes are required to prevent or reduce these long-term adverse outcomes | High (9/9) |

| Tosto et al. [63] | Determine the relationship between ADHD and mathematics | Mathematical ability, Mathematics achievement | Database inception – February 2015 | 34 | 2,000–10,000 | Narrative synthesis | – Majority of the included studies were of high quality – There was clear evidence for a negative relationship between ADHD and mathematical ability, which was stronger for inattentive compared to hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms | More longitudinal research is required to gain a better understanding of the mechanism behind this association | Moderate (6/9) |